It was a cloudy day in a November of my childhood when Uncle Ralph gave me my first carving tools. Of course, he wasn’t called ‘uncle’ yet, at the time, but never mind. I was probably about ten, and it was a rough time in my childhood, for a lot of reasons. If I’m remembering the correct occasion, he arrived without Auntie Lidia, alone on his motorcycle, round leather riding goggles pinching in the top of his hair while the rest of it flew out behind him. Even his beard flew along beside him as he rode down our driveway. He’d come by for my birthday, and I remember his wonderfully long brown eyebrows and much longer braided beard leaning down to me with a most beautiful leather bag held out in his dark hands that always looked more weathered than you might expect for a man his age. "Here. Got you this.” He said, and opened the bag to show me all the different types of tools he’d packed into it.

I remember thinking how annoying it was that he said he’d ‘got’ it for me, when it was clearly his own bag. Eventually I realized the gift had been much more special for having been his own bag, than if he’d just bought me something at a store. It was a piece of his heart. And he’d given that gift to me at a time I needed not only to be seen, but to have an outlet for my pain. I suppose Uncle Ralph’s outlet was creativity—often with carving—so he gave that to me.

Uncle Ralph was always carving. We’d be sitting at the beach and he’d pull out his pocket-knife and just start whittling a piece of driftwood. He even seemed to sometimes have a little carving in his pocket, which he’d randomly start working on, as we sat somewhere. The parents of our community built a playground for our new school, and of course Ralph was one of them. He carved a driftwood log into a horse that became burnished by a couple generations of children who rode to our adventures at recess. Ralph gave us adventure. He was a printmaker, as well, and once did a project with the older kids at school, where he taught them to make self-portraits in relief out of cardboard, and then together with them built a cardboard bus, in the windows of which the kids put their cardboard selves. Then he laid a giant paper on the bus, and drove a steam roller over it to make a print! I’m a printmaker too, now, and I don’t have to tell you why.

When I got married, Uncle Ralph carved a wedding bowl for me, and he stood up to sing for me and Markus. He welcomed Markus into his life without any hesitation or awkwardness. Just treated him like family, instantly. After we moved back to my home island, and spent more time with our family, here, and as Markus’ beard got longer and longer, I once suggested Markus might braid it like Ralph’s. “No. That’s his thing,” Markus replied. Uncle Ralph is so cool his style is untouchable. And yet he’s one of the most open and accepting people you could meet.

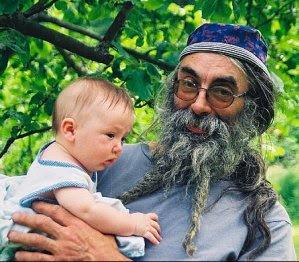

He loved children. Not in the way that fawning adults often seem to ‘love children’, with affection and concern and more than a little superiority. Uncle Ralph related to children as if they were equals. That might mean he said somewhat inappropriate things, at times, leaving us staring blankly, where his bald humour bewildered us. But it also made us feel seen. He had four of his own children, and eventually a bunch of grand-children, but he still had time and acceptance for all of us hangers-on.

When my son Taliesin was little, he had a knit yellow toque with ear-flaps ending in long braided strings and tassels. He quite correctly identified that this was the sort of hat Uncle Ralph would wear, and used to dress up in that hat, sometimes with colourful vests and scarves, and call himself Uncle Ralph. When Tali was turning five, and had been digging away at a hole near the driveway he called his ‘mine,’ Uncle Ralph and Auntie Lidia arrived with yet another unexpectedly perfect birthday gift: A shovel. He’d bought my son a small, light-weight, but very functional shovel, and carved TALI into the handle, in ornate capital letters. Tali’s own shovel, for his own mine. One year, Tali only invited four people to his birthday: Jon and Rika (similarly unique and close adopted family of ours), and Uncle Ralph and Auntie Lidia. Tali stipulated that Uncle Ralph must bring his guitar. So he did.

Uncle Ralph could be very loud and very quiet. At that small child’s birthday party he sat very quietly noodling on his guitar, creating a beautiful environment for our celebration. At other times he could be loud and even abrasive; shouting and joking and laughing, playing baseball, drinking beer, and dancing and dancing like you could never imagine his long hair tamed; his hands and legs quiet, or his face not wild. But also at a party—a big party—he was a safe place to go to. Often he’d be down by his creek, sat down by his makeshift barbecue, tending to his special salmon that everyone back up at the house was waiting for. I used to just go sit down there with him, quietly. Often it was just the two of us, maybe with an auntie or another kid. And he’d tell us about his plans and projects; the fish that were circling in a pool of the creek; any number of his amazing inventions. Or maybe he’d just sit carving, and then eventually hand us a beautifully decorated stick. We loved him.

Ralph became ‘uncle’ to us, really by word of mouth. He was one of a small group of cherished friends of my parents with whom we spent a lot of time, growing up. And at some point Gail told us she’d like us to call her Auntie. It felt like a gift, so I called her Auntie Gail, proudly. Then one day Lidia mentioned that if Gail was my auntie, then surely she was too, so, by extension, Ralph became my uncle. He never needed or asked for that name, but he also took to it like it had always been. I guess because it always was.

One day I was leading a class back from a forest adventure near Ralph and Lidia’s home, and I looked over their fence as we passed, to see him sitting on a chair in his yard, whittling. “Hi Uncle Ralph!” I called over the fence, and he looked up and smiled, as about a dozen of the kids I was with hurried over, hands and chins pulled up onto his fence, and shouted, “hi Uncle Ralph!!!” He just kept smiling, like this was nothing out of the ordinary, at all.

His hands kept working at the wood on his lap, as his eyes smiled out from his mess of hair and brows, and his lips called out the musical tone of his reply: “Helloo!”

It was maybe five or six years ago that I first knew he didn’t recognize me. I’d known he had dementia for quite a while, but it always seemed like a minor thing. He covered it up well, joking about his mistakes, and acting like they just didn’t matter. Maybe they didn’t; we knew him well enough to not feel too lost in the confusion, and we covered up for him, too. But that day at the store, I went up and gave him a hug, and I could see in his eyes that he was hugging me because it was the appropriate thing to do, not because he knew who I was. “Hi Uncle Ralph,” I said, and he answered, “can’t find where I parked my car.” He hadn’t driven for years, but he went on to describe a car he also hadn’t owned for years. I figured he’d walked down to the store, and when he started asking for Lidia, I knew he was scared, and just hoped Lidia was on her way to pick him up.

Lidia was the great love of Ralph’s life. I know from my own experience that living with a person like Ralph is adventurous and beautiful, and also challenging. And too, his love is profound. Maybe like a child’s love for his mother is profound. And in moments of uncertainty, Lidia was Ralph’s touchstone. This past Christmas, the last time I visited Ralph and Lidia before he went to hospital, Uncle Ralph wanted to leave the house he’d lived in for over forty years to ‘go home,’ but despite his confusion, he still spoke to Lidia as though he knew her. No matter where his mind went, she was at the foundation of his sense of security.

Just before Ralph died, lying small and thin and quiet, his feeble knees bent under the hospital blanket and his mostly white hair pulled back into a ponytail, he struggled to breathe even shallowly, but once in a while he shuddered, opened his eyes, and looked into Lidia’s, where she sat in front of him.

A few days later, after Ralph’s family had all gathered around and said goodbye, after his mind had carried its trove of stories and inventions to some other place, and his body had left the world we live in, I attended a paddle-making workshop that I’d signed up for many months before. We’d been tasked with finding some kind of learning or self-discovering in the experience of carving our paddles from 2×6 cut blanks. And although I struggle with following directions, I didn’t have to look for meaning, that day, because Uncle Ralph was there with me. As I pulled the draw-knife, manipulated the small plane, and eventually sanded my paddle to a nice smooth object, I felt enormous gratitude for this man who first inspired me to carve, but more than that, I realized that I was using carving to heal from the loss of him. In living, he gave me the tools to heal from his death.

Goodbye, Uncle Ralph.

He would say, ‘hey, bye.’