Last night I attended a devastating meeting in my community. On the surface it was pretty run-of-the-mill: A bunch of councillors and a few municipal staff members slowly picking their way through various presentations, decisions, and amendments. They came to the end of the meeting having checked a few boxes, put a few requests to bed or to progress, and made a few small changes to the contentious bylaw that much of the population feels will rip the heart out of our community.

As a member of this community for all of my life, I've been passionate about the things that tie us together. Some of those things are the big organized events, like our traditional summer festival and Remembrance Day celebration; the fishing derbies that used to happen when I was a kid, and the raft race. The events change over the years, but always hold us together, and are facilitated by a huge number of dedicated creative people, who look at their community and see the need for celebration. We're also held together by the little things, like stopping to chat with an oncoming driver in the road, or letting the community cat into the car for a ride. We're held together by actions like calling a neighbour for help clearing a dead deer or sitting down with Bob for an ephemeral but deeply interesting conversation.

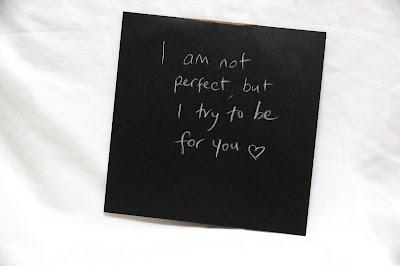

Sometimes the holding together is very intentional. So many of us contribute time, ideas, and great heart to this community. In my own work and volunteer roles, I've been bringing newcomers into engagement with our wilderness, so that they can love and value this place as I do. As an artist I've grown in this rich stew of community to see the value of social practice around inclusion and diversity. I consider my work (both public and gallery-focused) a method of bringing out the voices of my fellow citizens and reminding us all of our personal benefit to community.

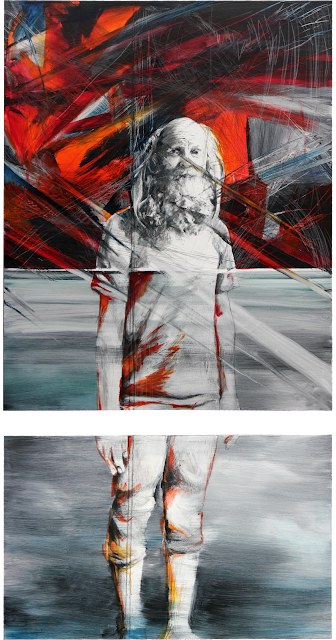

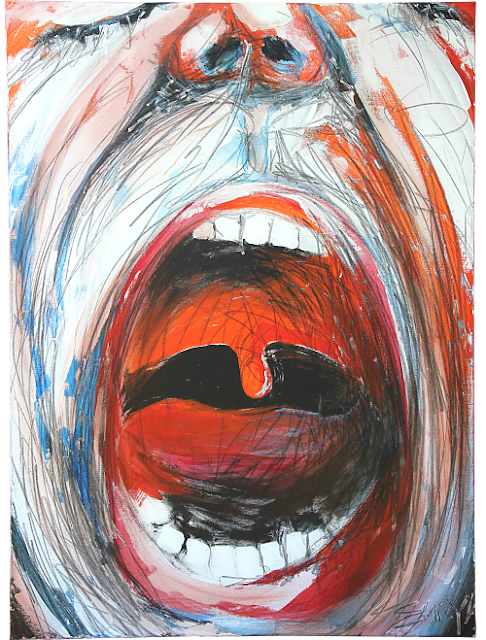

Most of the artists I know are somehow engaged in broad community visioning, and feelings are our language. When we sit around talking together, we talk about the big picture. We talk about the vibe of the public spaces in our community, and the vague drifting of public sentiment; of community values. We talk about the social-emotional gorgeousness we're trying to promote, and the social change that is or should be happening. We see the big web of emotional connection that makes a community whole; that tethers us to the place we live, and we work in our sometimes-mysterious ways to keep it alive.

Yes, these feelings and ideas can be vague, but we are masters of vaguery. The term "vague", like its linguistic origin in the French for "wave", might seem unthreatening. But a wave, however gentle, rarely comes alone, and sometimes builds slowly, unseen. Sometimes a tidal wave is a wall of water. Often it's just a going out of the tide, and then a returning, and returning, and returning, until the one unappreciated wave has enveloped a whole community. "Vague" is the feeling of community sentiment, and it can be just as devastating.

What devastated me about the council meeting was our council's lack of vision for that social web; that vague sentiment. During the meeting, various councillors mentioned that the bylaw was needed in order to "control" people, and that "not all people are our friends". They spoke often about controlling the population, but never about listening to it. They received a long series of letters asking them to consider the social damage caused by a pending bylaw that will severely limit access and enjoyment to our most popular public spaces. Letter-writers spoke about the casual gathering that will no longer happen after this bylaw is passed, and the councillors chalked it up to a lack of understanding on the public's part. The one councillor who opposes this bylaw spoke up to explain–again–his fierce opposition, and the idea that they shouldn't be pushing through a bylaw that is so publicly reviled. They carried on without acknowledging his words. Finally, they picked away at some of the wording of the bylaw, ostensibly to help people understand, without seeing the big picture. They didn't let any feelings they had to get in the way of their bylaw. They deafly ignored their populace, and carried on as though nothing had happened.

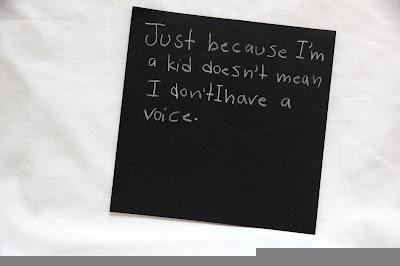

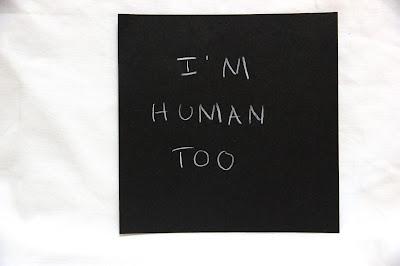

Is this a crisis of imagination? Maybe. Maybe we as a society are becoming less and less able to imagine a future we want to live in; to envision it so that we can create it. We're less and less able to see a future that is inclusive if we can't imagine how to converse or get along with those who we deem "not our friends". We know, in the abstract, that we need public policy that is expressly inclusive, but we, like our councillors, have forgotten how to include our neighbours. We've forgotten how to listen to the great vague voice of public sentiment.

The big picture in public policy is public sentiment. The public doesn't like this bylaw. We don't like that we haven't been consulted. We don't like that our letters were not read aloud, nor discussed for the many serious points they bring up. We don't like the feeling that a series of long complex bylaws will govern our footsteps and enjoyment of community spaces. We feel oppressed by this bylaw, and our feelings are what this community is made of.

As our community becomes more and more developed; more populated, more busy, more anonymous, we're losing sight of the importance of neighbourly compassion in our social exchanges. As our municipal government takes on more control, we have relinquished the desire to affect change, ourselves. We've given up. We are increasingly more likely to call the authorities to deal with dead deer or fallen trees instead of hauling them away, ourselves. We used to use them for meat or firewood; we're no longer permitted to do so. And as our social agency is taken away, we're growing more likely to call the authorities when a neighbour offends us than to bring over a drink and have a chat. Our crisis of imagination has led to a crisis of public agency.

And when I realized that the vision of that big picture–that public engagement–is missing from our leadership, I realized that we also have a crisis of feeling. We elected leaders to do a dry job of picking through legal documents and approving or rejecting requests, but we didn't empower them to feel. When they post on public forums they are expected to remain impartial. We expect that the work of governing should be done without emotion, but it concerns emotion a great deal. We need our councillors to have compassion for the woman living in a tent behind the library, to prevent them from passing bylaws that would outlaw her presence. We need them to notice the people feeling alarmed and horrified by proposed changes and ask themselves how those feelings will impact the big picture of our community. We need them to feel, so that they can take our feelings into account; so that we feel heard and empowered to engage in our community.

Originally published in July, 2021.