This story is also available in audio form, with pictures, on MakerTube.

Dear little Emily,

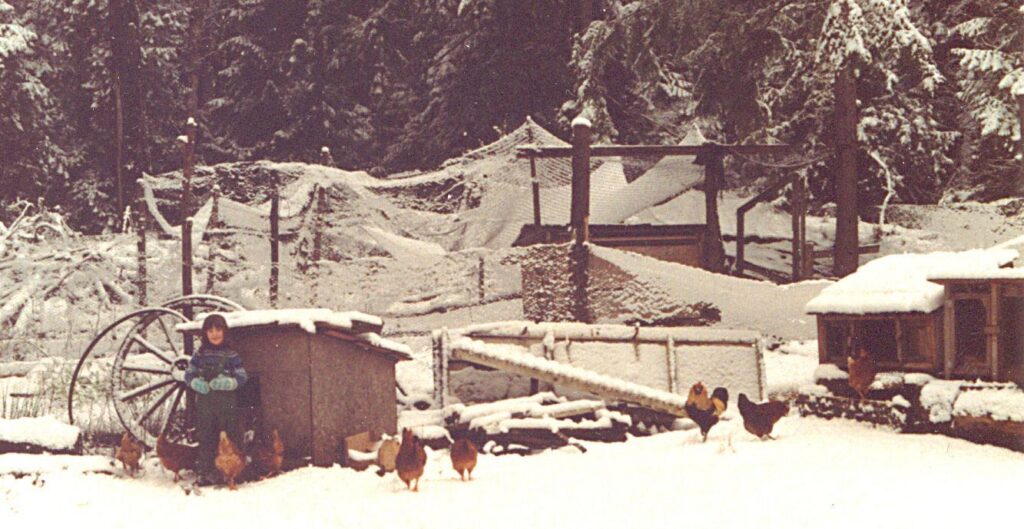

Today, when you’re almost ten, my little old self, you’re sitting in the dark sparkly sand by the waves lapping. Barnacled rocks poke up from the sand into your thighs, but you don’t care. You have Pappa’s sweater on over your swimsuit, and you’re fine. You hear Mum’s guitar up on the beach, and she mutters that her fingers are too cold to play, even though the fire is right in front of her. It’s September and the family has gone to the beach, maybe for the last time, this year. It gets dark so early right now that it feels almost like Christmas, even though it’s 8pm, and you haven’t gone home for dinner. The end of the box of Old Dutch crackles between Adrian and his friends as they sit around the fire. The aunties are chatting and you can’t hear what they’re saying, but Pappa’s laugh breaks the night for a moment. You’re waiting for the stars to come out, and your heart sings,

Oh watch the stars, see how they run!

Oh watch the stars, see how they run!

Mum stops playing her guitar with a definitive hand-thud on the wooden body, and announces it’s time to go home. It was supposed to be sunnier, today, or at least you thought it would be, when it was sunny this afternoon, and you dug up the potatoes in just your t-shirt and shorts. Your bare feet had carried half the garden in with you, Pappa said. Now you’re washing them in the course gravelly sand, and you don’t want to go home.

The stars run down, with the setting of the sun.

Oh watch the stars, see how they run!

Home is a glorious converted trailer, that Pappa renovates every few years to add a little more to your bedroom. Home is where the sun peeks up over the cedar trees to come flooding slowly over the veggie garden at ten, on autumn mornings, spreading yellow over the dewy grass and the starting-to-brown veggie tops that haven’t yet been harvested. Home is where Mum does canning projects with you; sometimes they’re delicious and sometimes nobody wants to eat the zucchini pickles. Remember that year when you slipped on the log of the lettuce bed and fell splat in front of the rooster and he jumped on your face, and you were bleeding? Well I’m fifty, now, and I still have the scar. Mum said it was because he was an Araucana, and they’re so vicious. You avoided him after that, and warned your friends away from him, too. I wish you knew about Splashy.

When you’re in your forties, your teenage daughter is going to ask to get chickens. Partly out of motherly encouragement, and partly with a giddy childish excitement, you’ll agree to your daughter’s plan, and buy twenty-nine fluffy little chicks, who will spend their first few weeks in a makeshift brooder in your daughter’s bedroom, while the whole family works to finish the best-chicken-coop-ever.

This will be your first experience of “chicken math”, as you’ll later learn to call it. Chicken math, apparently, is when you calculate that eight hens and a rooster would be perfect to keep your whole family in eggs for most of the year. Of course you’ll need twice that many chicks, since half might be roosters. So sixteen, then. Seventeen for good measure, just in case. And you’ll make sure to get some winter-hardy breeds in the mix, so you still get eggs when it’s cold. The mix. Since you want a mix of breeds (brown eggs, pink eggs, blue eggs, and green eggs!) you really should hedge your bets and get at least four of each type, so there might be at least two hens of each breed, after the initial rooster cull. And since you’re buying so many breeds, well… twenty-four isn’t such a bad number, right? It will be twelve after the cull. Approximately.

Breeders are also approximate. And generous. So somehow the number will blossom from twenty-four to twenty-nine by the time the adorable little peeping boxes of fluffballs arrive. Whatever. Chicken math. More meat in the freezer, you’ll say to yourself. And by autumn you’ll indeed have plenty of meat in the freezer, as well as thirteen hens and two roosters. Lester Clark because he’s big, and the Splash, because he’s so cute.

There will be two Ameraucana chicks in that brooder in your daughter’s bedroom, and you’ll spend extra time with them, because they’ll lay green eggs. One of them will turn out to be a mean little hen, and eventually die of some sort of undetermined internal ailment. The other will be a rooster. Despite being very close in genetic heritage to that rooster who gored your face in the garden when you were little, he’s not vicious. He loves you. You will eventually figure out that he’s infertile as hell, though unfortunately you won’t realize this until after Lester Clark pecks his right eye in, and after you kill that giant mean Lester and eat him even though his meat is tough.

You will realize Splashy’s place in the family one day after his pecked-in eyeball will have risen back into its socket, and there in the sunshine of the day will be a giant squawking fracas in the chicken coop. You’ll run into the coop to find Lester Clark just standing there like a giant oaf by the coop door, Splashy having an epic battle with a giant red-tailed hawk, and all the hens crowded with their faces pressed into the corner of their house. Godiva, the actual boss and Splashy’s faithful companion, will be leaning with her back against the other hens, wings spread open to cover them, screaming wildly in the direction of the hawk. In a moment of adrenaline-fuelled foolishness, you’ll grab the hawk off of Splashy and throw it out of the run. You’ll pick up your sweet bloodied rooster and nestle him into your arms. Godiva will release the hens to their business, and Lester Clark will have his neck slit and end up as stew.

So there you’ll be with eighteen hens, and just infertile little Splashy to protect them all. (Yes I know, I said thirteen, but suddenly there will be more chicks, so… chicken math.) Splashy will originally be called ‘the Splash’ because he is a ‘splash’-patterned Ameraucana. You know, like you might call your neighbour ‘the buzz-cut guy’. But the hawk incident will reveal that this little scrappy black and white dude is in fact The Splash. Not just the only splash-patterned chicken in the flock, but also the feeder of delectable grubs to the hens, the protector of chicks and brooding hens, the announcer of sunshine in the morning, the afternoon, and the moon in the middle of the night, the hunter of rats even in the pitch black, and the faithful companion of Godiva, who is the boss of him, too. Splashy will be The man.

Splashy, despite incongruously being an Ameraucana, will be the only chicken ever in your life who actually wants to be picked up, and when nestled into your adult arms, will promptly fall asleep—always, and without fail. His little whitish eyelids will sink upwards to close, and he’ll murmel his beak like a little old man, contemplating. He’ll need to rest from his constant vigilance over his flock, and your arms are the only place he can do that, most of the time. He’ll become your little love. He’ll hop up on the box outside your bedroom window, crane his neck inside if the screens are off, and crow into your face until you get up, scratch his tiny little wattles, and tell him good morning. Then he’ll go back to stomping circles around the younger hens, herding any potentially-broody hens into nesting boxes, and having his head checked for mites by Godiva.

It’s always a special day when eggs hatch. You’ll know it’s time, because chickens’ hearing is much better than yours, little Em, and they’ll all be standing around craning their heads towards the nesting box for a few hours before the first chicks pip. As hatching days go on, the best brood hens will chase every other chicken away, besides Splashy and Godiva, the undisputed leaders of the flock. And they’ll come and go, eating some chick feed, rearranging some bedding, and often just standing silently, listening to the peeping from under their broody flock-mate.

After a few days, when the hen emerges with her brood, Splashy will stay nearby, standing sentinel between her chicks and any potentially-ill-intentioned other hens. He’ll support her and her chicks until they’ve grown big and independent, running freely all over the yard, digging up your veggies, and roosting in trees that the older chickens can no longer fly to. After a while, Splashy will start chasing away the little cockerels, until eventually you’ll move them to the bachelor pad, before slaughter day.

Slaughtering is not something you will ever enjoy, little Em. I know you’re semi proud, right now, that you can butcher a chicken or rabbit without help, but you don’t have to do the killing yet, now you’re only nine, and Pappa still kills the livestock for you. He’ll teach you, of course, eventually, to kill your own meat. But all of your life until you’re me, now, at fifty, it will still be hard to do. I think I turn off my heart to do it. Slowly. That’s why we have a bachelor pad, now. Practically, the separate run for roosters is a means to feed them their own high-protein feed, and keep them from fighting for a few weeks while they put on some meat before butchering. But it’s also the place I harden my heart against them. I distance myself as I bring them treats. I stop calling them “my love” or “sweetheart”, and I stop loving them.

When slaughter day comes, I take them to the cone, and get the job done, silent tears falling, but no big fuss. They’re just meat, now, as Mum says to you. We’ve learned to do this more humanely, now, settling the gigantic feather-monsters into a big aluminum cone, and gently guiding their heads to hang out the bottom, where I slit their necks until their blood runs straight into the bucket, below. They bleed out in less than a minute, kick their legs mindlessly as their muscles lose contact with their brains, and die. It’s a lot less traumatic than the way Pappa does it, holding them against the ground and chopping their heads off against a board, then holding their flapping, kicking bodies away from himself, as the blood spews. You’ll learn to do that too, of course, before discovering the cone. But the cone will be a relief. A small bit of mercy in a horrible job. But, as Mum and Pappa always say, if you want to eat meat, you need to accept that you’re eating an animal. You need to kill.

Splashy never went into the bachelor pad, of course. He walked around to look at the young boys in their new digs, but he never went in. I always wonder if he knows where they’re going, even though we take pains to never slaughter within view of the other chickens. It’s funny we call these choices “humane”, when humans are probably the least compassionate species ever to exist. Not true, Splashy would say, as he tilts his one good eye up at me and clucks. He loves me, and as of now, I know he thinks I’m compassionate. Or at least he did when I killed him.

For the past year, Splashy’s had some kind of neurological problem, we think. A few times, he ended up upside down on the ground, just looking around him, but unable to right himself. Like a June-beetle fallen on its back. The hens just stood around looking at him, until we found him and set him upright again, and he just walked away as if the day was fine, stomping his feet around his favourite hens, in circles.

But these last few weeks he’s been going to bed early, and then eventually he stopped sleeping on the roost, choosing instead to nest on the wood-chipped floor outside the nesting boxes. Again and again, we found him there, with Godiva standing guard over him. His legs seemed to get weaker and weaker. He tumbled down the ramp out of his house in the mornings, rolling onto the ground and then getting up to go outside like all was well. Falling off stairs and down hills just became his way of getting around. He still found insect snacks for his ladies. He still kept his good eye trained on the sky, watching for threats as the flock foraged. He still came over to see me when I checked on him. Until one day he could barely get up at all, so we took him inside for the day. The autumn sun came out, outside the house – the same house you live in now, little Em, and where I’m still raising chickens, now. That golden light tumbled through the foggy yard and onto the browning veggies; the celery tops curling against their weakening stalks, and the empty squash vines shrinking away into the dewdrop-lit grass.

I brought him in every day and cuddled with our Splashy. I called him “my sweetheart” and “my little love”, and he closed his eyes and leaned his beak against my cheek. Pappa came by and saw him sitting in his box in the living room. He said it was cruel to keep him alive like this, and I knew he was right. But I couldn’t bring myself to kill my Splash. Not this rooster. So again, we carried him out to the chicken house and put him to bed on the chips. Godiva came to stand by him again, and he pecked her, sending her away. He slept alone. The next day he couldn’t get up at all.

That day was beautiful. The dew dried right off the whole yard and the sun warmed everything. The light was orange, almost like during a wildfire, but pinker, too, this time, like it was beckoning Splashy to join it. I laid him on the grass and brought him blackberries and other treats. He shared them with all the older hens, pecked the younger ones to keep them at bay, and Godiva never came back to him.

As the sun set, Splashy’s flock took themselves to bed without him, and he looked up at me with his one good eye. I knew it was time, but I didn’t know what to do. I asked our partner to bring me the sharp knife and a towel, and then I just sat there in the deepening evening with our brave little man on my lap. Our partner dug a hole next to the chicken run, where Splashy could always be close to his flock, and I said, “should I kill him at the side of the hole, on the ground, or in my lap?”

“I don’t know,” our partner replied. We were both empty of reason and joy.

I decided the hole was more practical, so I knelt down beside it, the knife in one hand, and my little white splash rooster in the crook of my other arm. I laid him down against the ground and he gave a huge flap, writhing his whole body as if to save himself. I was so alarmed and upset I jumped up, saying, “oh no!” And “I can’t do this!”

Then I sat back on the chair we’d been in for hours, letting Splashy settle back onto my lap. He looked straight in my eyes, and then rolled over on my lap, stretching his legs and breast out as far as he could. He stretched his neck out too, baring his throat to me, and waited. I held the sharpest knife against his throat, and in a rare and awful stroke of misluck, I failed to cut through his skin. Horrified, I gasped, and he just lay there, still waiting. With our partner’s help, I gathered my nerves and killed the most sensitive, beautiful, brave and clever chicken I ever knew. And we shed a million tears as we buried him there with a heap of autumn marigold flowers and yarrow leaves.

It was so dark by the time our Splashy was buried, that we stood in the damp evening, looking up together at the darkening sky, waiting for the stars to come out. Our partner put his arms around me and we just stood there, looking sometimes at the darkness at our feet; sometimes into the deep, deep blue. And in the safe arms of my partner, I sang,

Oh watch the stars, see how they run!

Oh watch the stars, see how they run!

Oh the stars run down, with the setting of the sun.

Oh watch the stars, see how they run!

The sun still came up the next day. Some small animal dug at the dirt over where Splashy was buried. We planted giant allium bulbs with him, and they’ll bloom next spring. At the time I’m writing to you, we’ve already introduced a new rooster to the flock, and he’s learning his boundaries from the hens. Godiva ignores him.

Little Emily, this life is full of so much pain and so much beauty. If a chicken can teach us about acceptance and love, then there is hope for our world, despite the sometimes bleak odds. The darkness falls and somebody still crows, the next morning.

Love, Emily