"Children are the most disrespected group of people in the world."

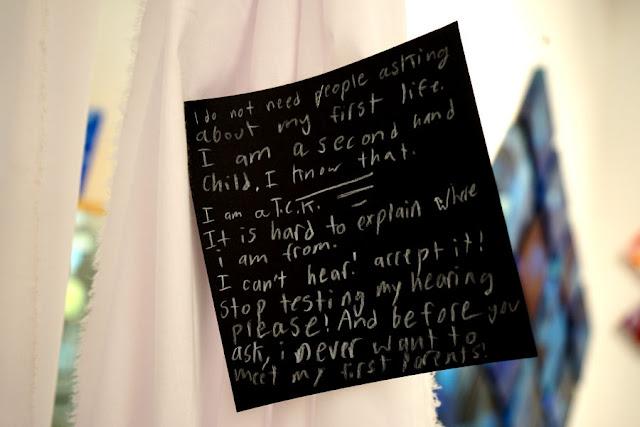

She turned her small face and looked at me intensely, maybe to see how I would react; maybe to be sure I heard her. She was one of a group of three teens who had just come through an installation about children's rights and left her comments behind. I hoped she felt respected by me as she walked out of the gallery.

And then it hit me: "Group of people." That's how we see them. We see them as separate from us until we judge them to be old, wise, or experienced enough to earn our respect – as adults. We determine their clothing, their food, their education and other activities, their freedom to come or go and quite often we even determine their friends and hobbies. They tell us their fears and hopes and great big plans and we pat them on the shoulders and ignore them; carry on with our lives. When do we look them in the face and ask them to tell us more? When do we ask their advice? When do we heed it?

I grew up and eventually returned to raise my kids on a small island. For longer than I've been alive, the teens from this island have boarded a ferry five or more days per week to attend school on the mainland. Unchaperoned. As a teen I got up at six-thirty, washed my hair under the tap, dressed, put on my makeup and left to walk to the ferry at seven. In the winter I arrived at the dock with my hair frozen like brown sticks around my face. Unlike some of the other girls, I did not push into the crowded washroom to fix it in the two tiny mirrors. I sat at the end of my age-group of kids, watching the same kids get beat up day after day, watching the animated conversation of some girls I wasn't friends with, picking at the Naugahyde seats and avoiding the splash of the food fights. I moved further down when people started bringing compost to throw.

Twenty minutes each way. Morning and afternoon. The ferry commute was a drag, and a shared ritual, and also the rocking, floating bridge between the confines of childhood and the expected freedom of adulthood. In the 80's we skipped school by going en masse to the mall first thing, then arriving at school before lunch to report that we were all late because the ferry was late. We sometimes argued about the ethics of how to accomplish this feat. We shared time every day, but we were individuals. We had different stories, different values, and different lives.

Our island also has a history of ferry exclusion. As a public-private entity, the ferry corporation has the right to ban people, and they have done so on various occasions that I remember. They banned a teenager in my grade for vandalism and mischief. He eventually took the ferry with a chaperone to attend school. They also banned our local petty criminal because the police thought it would do him good to get out of the community where he regularly slept in parked cars and picked drunken fights in public. It didn't help. Community members transported him back to the island in the trunks of their cars. My point is that these people, too, are individuals.

At various times we've had issues arise on the busiest ferry runs, like unidentified persons vandalizing the boat or flooding the toilets, and sometimes the first response is for the captain to make announcements to the teens. He tells them, as a group, to smarten up and behave themselves. He tells the adults on the next commuter run to rein in their children. Recently people in the community have been wondering aloud in public why teens (again, as a group) can't just behave themselves for twenty minutes at a time. Few, if any of us, know what the current transgression is, but we know it's been committed by teens. The captain has reportedly announced to our teens that if the unnamed incidents don't stop, the police will be involved and the surveillance footage will be reviewed. For me that crossed a line.

If criminal acts are being committed, it's perfectly reasonable to check surveillance footage and involve police. It's perfectly reasonable to expect people not to commit such acts, and to take steps to ensure that they stop. It is not, however, reasonable to reprimand, admonish, threaten and sometimes (as I have witnessed) deny service or civility to an entire group of people based on the premise that one or a few of them are suspected of having done something wrong.

When adults smoke on the ferry (which is wholly a no-smoking/no-vaping zone), they are asked to butt out. If they refuse, they are taken to the chief steward's office and spoken to, as individuals. I've seen this happen. I've stood at the chief steward's office while an adult smoker was being spoken to, and every effort was made to treat me with respect and provide me with service despite the fact that I, too, am an adult. The same can't be said for our teens' experience. Every teen is a suspect in some people's reasoning.

What do you think that does to a person? Imagine if every day you walked to work only to be eyed suspiciously at the door to the building, and every time a toilet overflowed, people called all the adults in the building together to reprimand them. How would you feel about using the toilet? Imagine if, when some person stole from the vending machine, they denied all adults access to the vending machines. Would you respect the people who judged you? Would you still care about upholding the values of your community if you weren't expected to uphold them anyway?

I'm responsible for denigrating teens as a group, too. When I was barely more than a teenager myself, a truck full of students from a nearby high school pulled up to my grandmother's lawn, dumped an assortment of fast food wrappers out the window, and drove off. A few years later, walking along our island road with my four-year-old son, we spied some litter in the ditch. He immediately shook his head and muttered grumpily, "ach… teenagers". I can't remember how I led him to that assumption, but I am certain I did. Now he's seventeen. He and his sister have somehow managed to get through a bunch of teenagehood without dumping their trash. Even more than navigating teen years myself, parenting teens has taught me to see them as individuals.

Teens are worthy of our attention as individuals. They are humans learning to be adults, and counting on our respect and exemplary modeling to help them navigate their surprising, sometimes frightening individual journeys. If we want them to see adults as individuals rather than a homogeneous, brooding group, we need to model to them how to do that. We need to see them, and we need to show them how seeing people is done well.

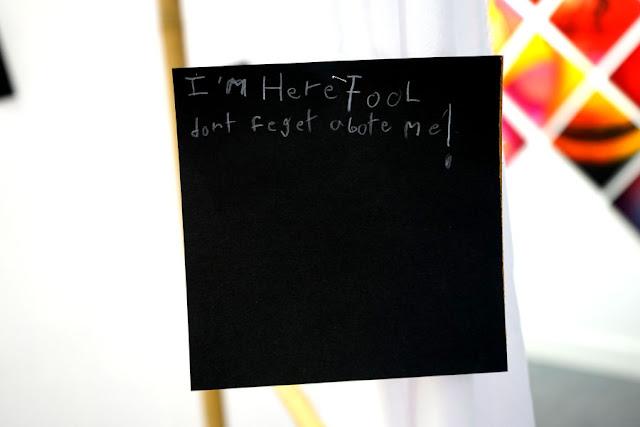

Some teens are children. They have an innocent wisdom not yet drawn out of them by the pressures of growing up. Some teens are also adults. They know their own minds and they know when they haven't done wrong. Some teens see us when we're wrong, and they know when we aren't hearing their voices. Some teens know when not to bother speaking up, because we've lumped them all into one disrespected group and we can't hear their individual cries. In fact, when teens report crimes committed by adults, they are often ignored.

It's time we look into the faces of the children and teens we pass and see them as simply humans. It's time we see them as individuals with wisdom, needs, values, and human rights. It's time we respect them.

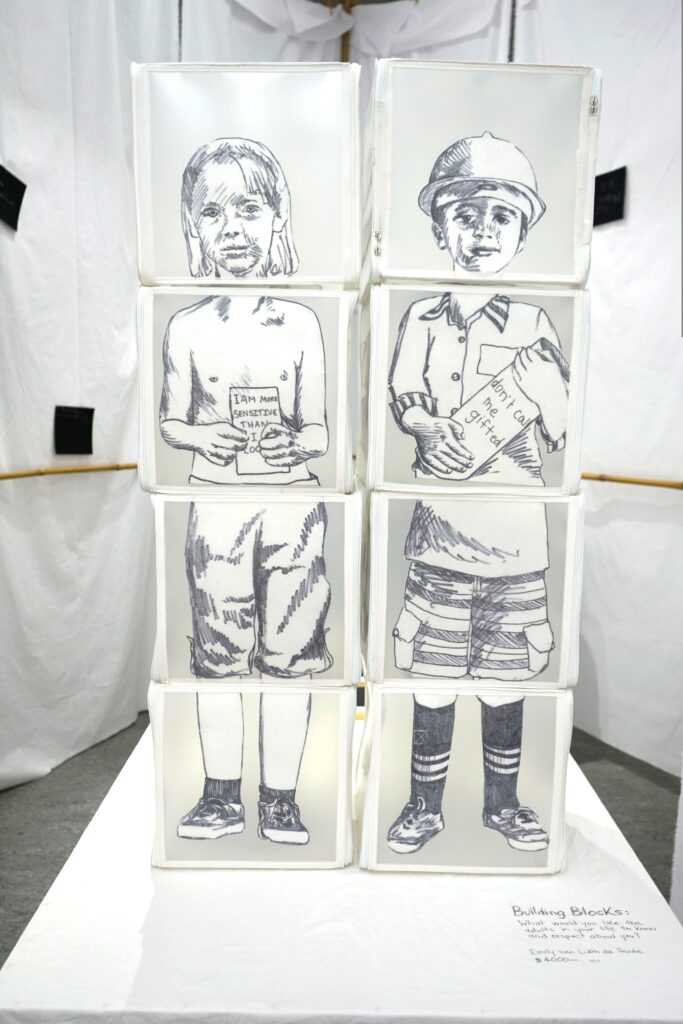

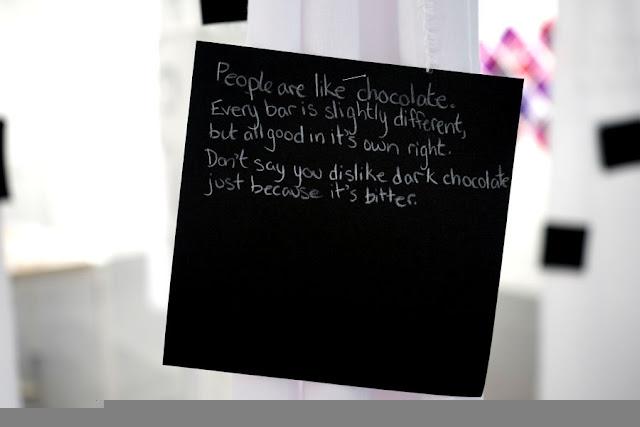

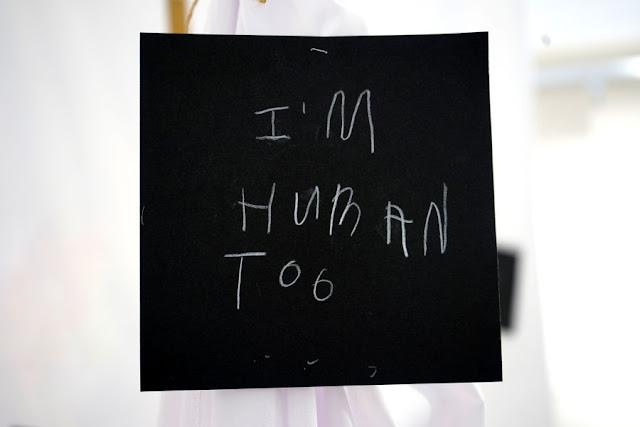

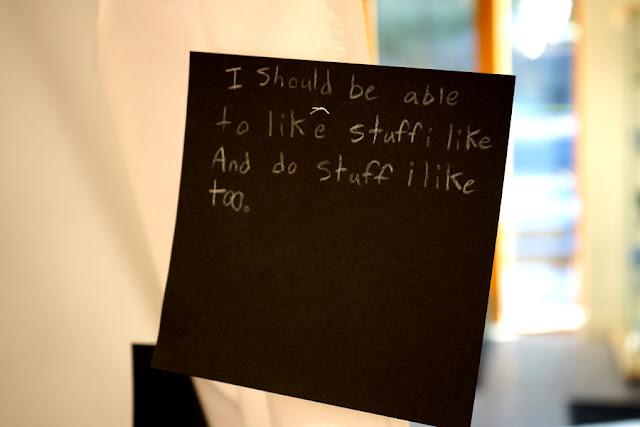

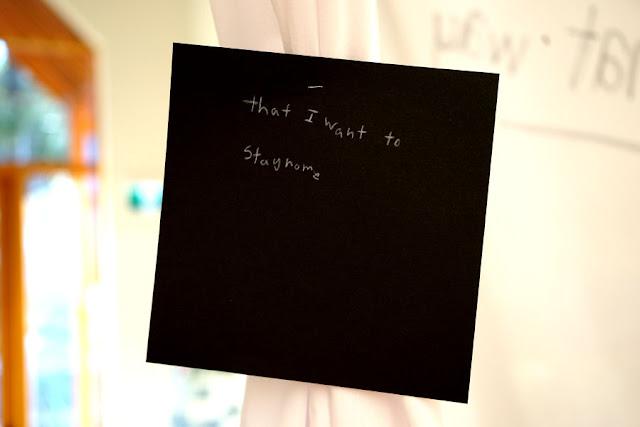

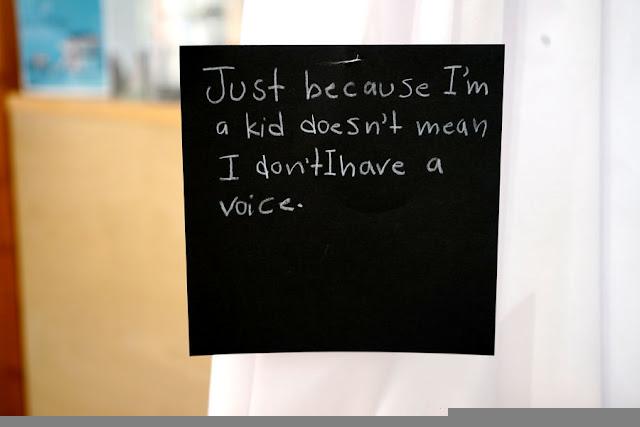

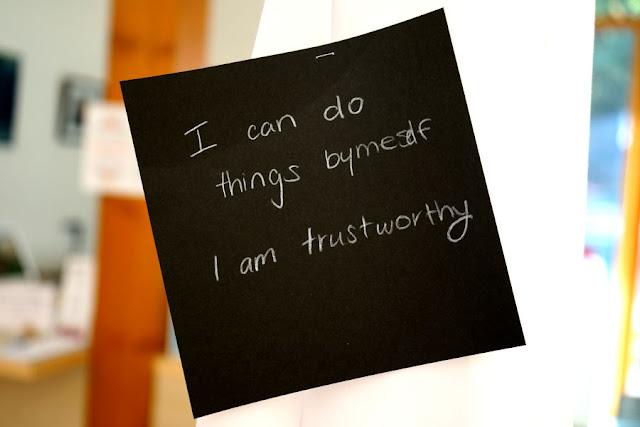

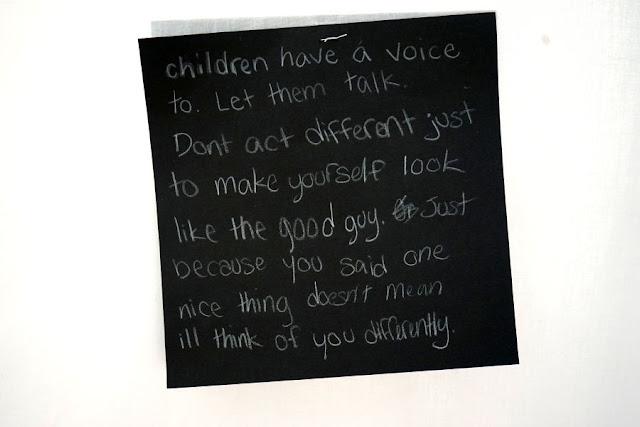

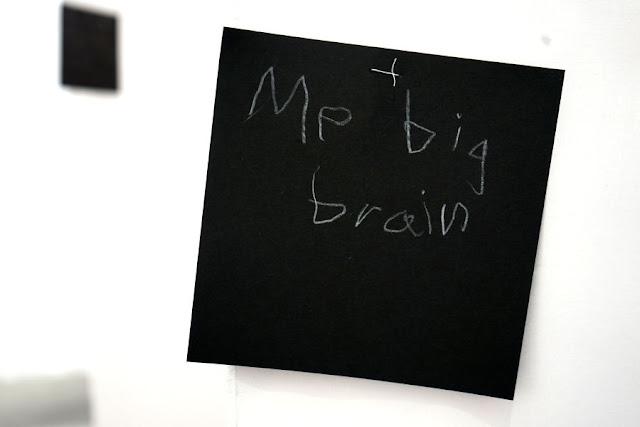

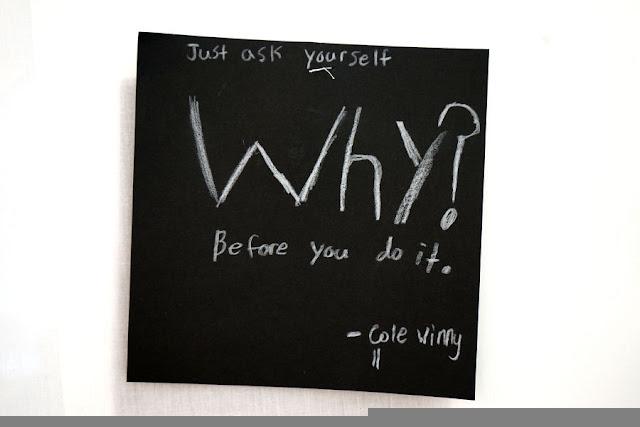

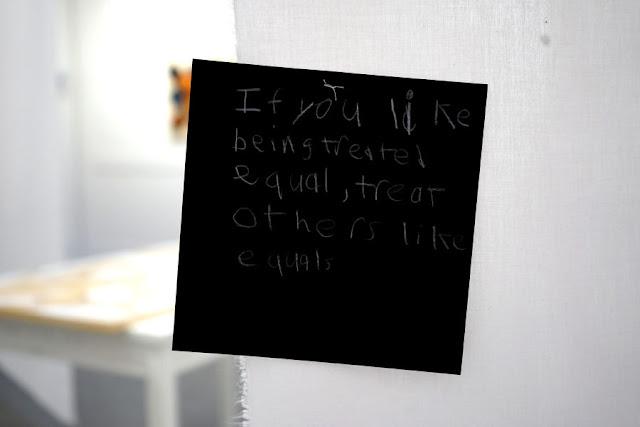

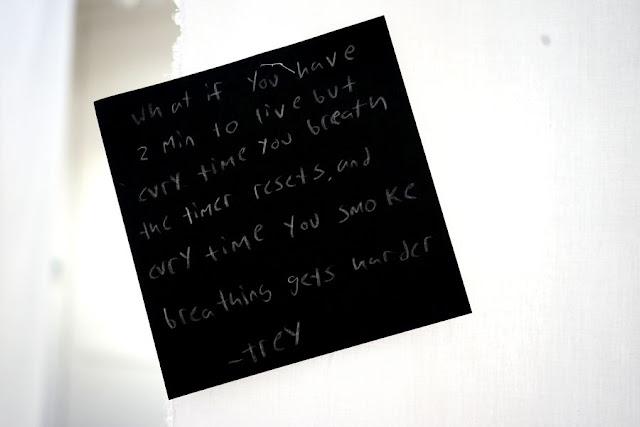

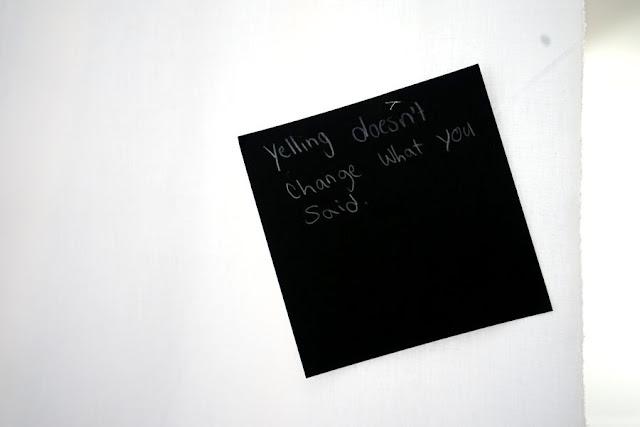

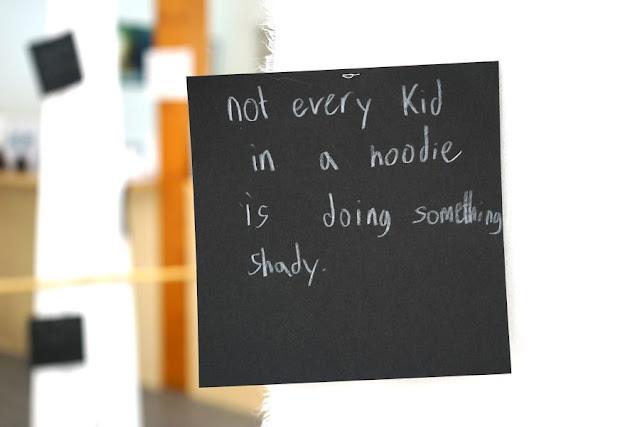

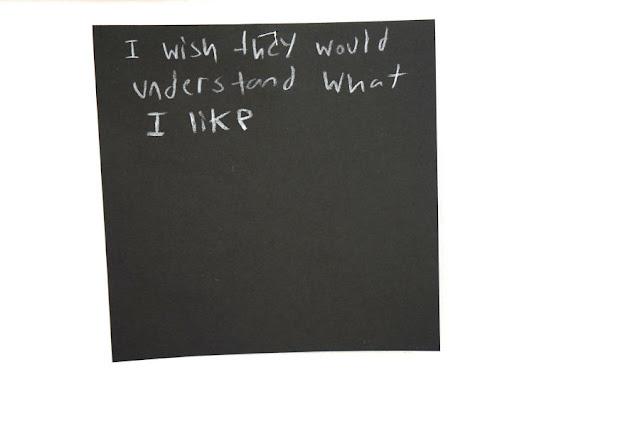

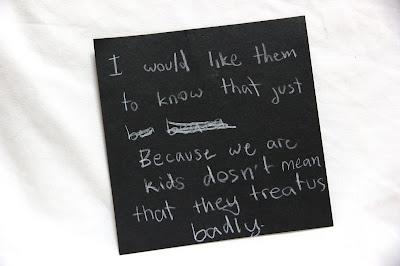

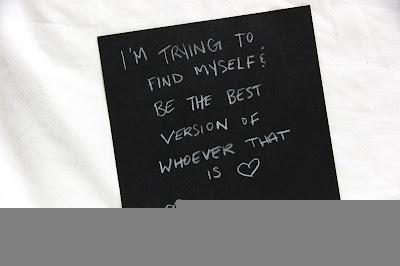

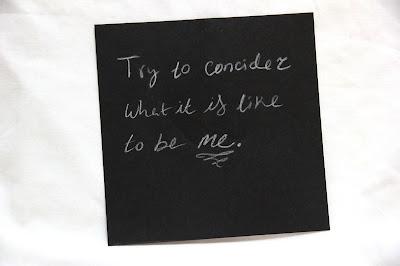

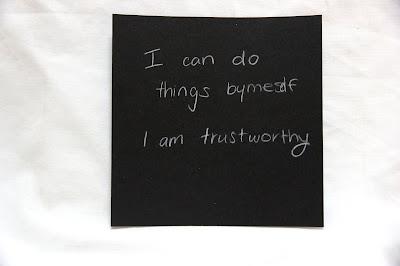

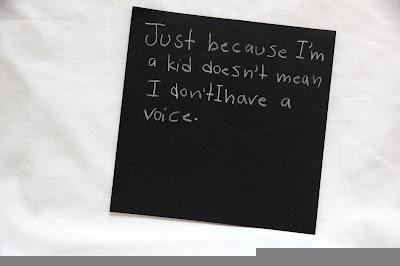

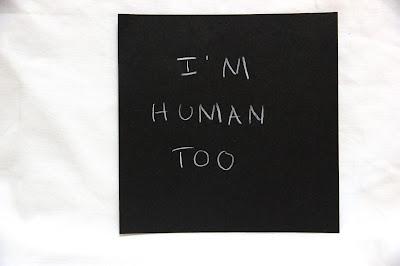

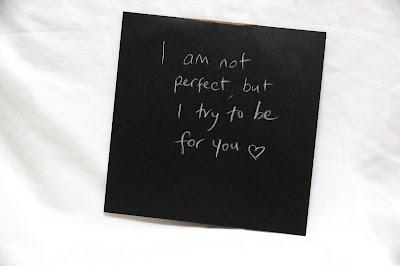

*The handwritten statements accompanying this article were contributed by teens at a 2019 installation of a piece called "Building Blocks: What do you want the adults in your life to know and respect about you?"

Originally published in October, 2019.