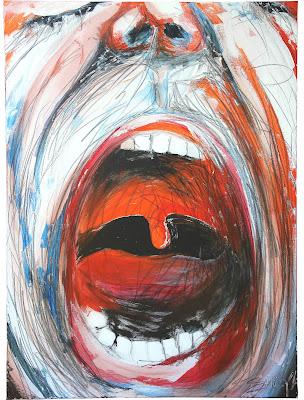

Tripping a little over an unexpectedly-high tuft of moss on the log I was stepping over, I heard shouts from the children, up ahead, and looked up to walk smack into the dangling tips of a soft wet cedar bough. I brushed the water off my face as the shouts were joined by gasps of horror or awe, and then guttural, powerful noises, and a loud “YEAH!!” As a small arm jutted up above the ferns that still stood between me and the kids, holding a rather long piece of deer-spine, that then fell apart in mid air, dropping a piece of itself unceremoniously back to the forest floor. The kid holding it up looked a little disappointed, but continued smiling, as they and their classmates experienced what was, for some, the first sight of a nearly-complete deer skeleton.

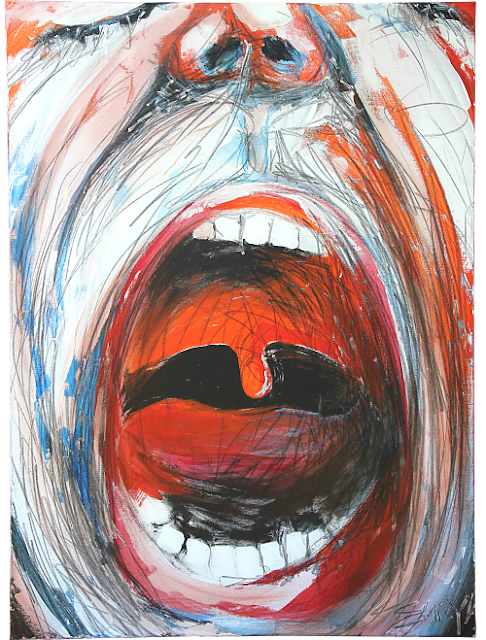

Some of the kids gathered as many bones as they could carry; some fought for their perceived rights to the skull; the spine; those amazing paddle-like shoulder-blades that always seem to become useful tools in the hands of ten-year-olds accessing their powerful, primal nature. Some stood back looking alarmed, and one kid was wearing the pelvis as a hat. A wide-eyed girl ran up to me with a piece of the bottom jaw, pulling a tooth back and forth in its socket. “It comes out! Emily, the tooth comes out!” She exclaimed. “It comes out and it fits back in!” Was she amazed by the perfection of the way bones fit together, or by the access to an understanding of her own teeth; those things that had come out of her mouth with some celebration, and then grown there again, anew? Maybe she was just amazed at the tactile delight of it all.

Tidying up today for this weekend's open studio, I dusted around my bone collection, as usual. There were a few dead flies on them, as well as a few spiderwebs, and thankfully not too much dust, because dusting feathers—and especially that desiccated dragonfly—is a pain! Every time I pick up the rat skull, one of its massively long curled incisors tumbles out and I have to slide it back into that channel that grew to fit it perfectly, when the rat was alive.

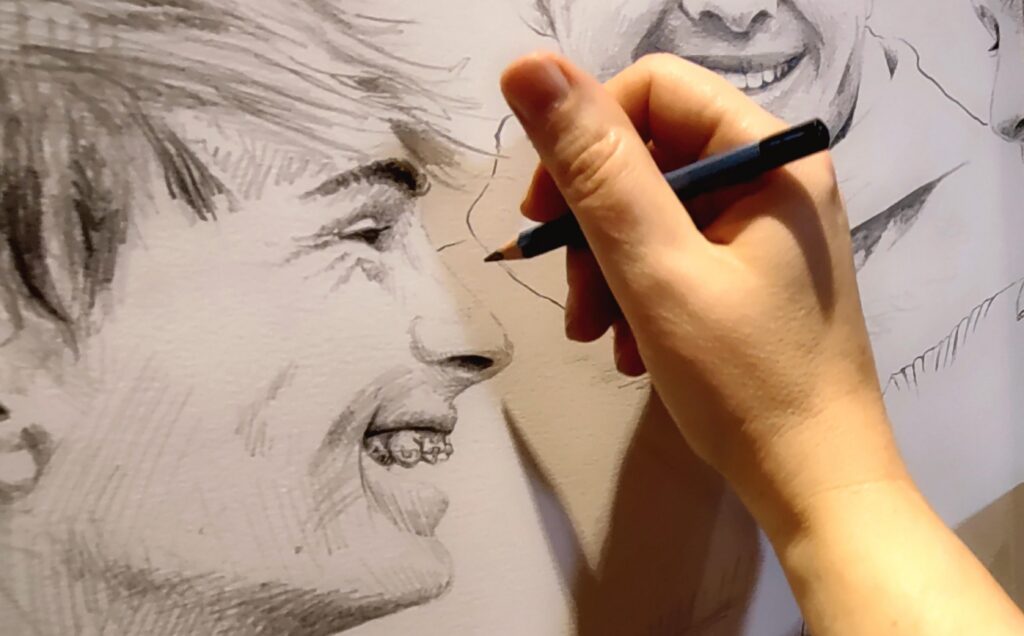

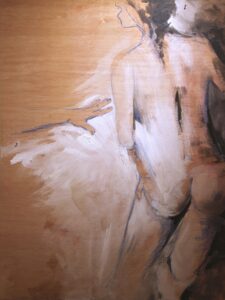

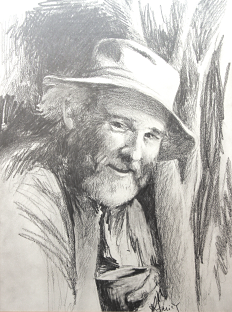

Most visitors to the studio just come to buy a painting and don’t even seem to notice the bones, but I want them to look clean, anyway, because there’s something kind of yucky about dusty bones that’s improved by being cleaned. And anyway, sometimes people do notice them, and ask about them. I'm always a little nervous to divulge that I actually almost never draw or paint from these. Some people assume I do, and I guess I might think the same of another artist; imagining her like Georgia O'Keeffe, describing all the beauty of these things in charcoal and paint. But no. They mean so much more to me than just a subject to make a picture of.

When I clean the bones, I’m reminded of their differences and similarities. I have a rat skull from the compost (caught by our cats and delivered there to decompose, by me) and a beaver skull that my brother found down by the creek. Both have those amazingly long, curled incisors. You can imagine how, as the rat chews away at the wood of the chicken coop, or the beaver gnaws the trees down by the creek, they’d wear them away and need that long reserve to keep growing in. It also reminds me why it’s so important to give pet rodents something to chew. Compare that to the teeth in my deer skulls that look more like barnacles; not meant for cutting through wood at all, but just gnawing on their tough fodder of grasses and my roses, if the gate is left open. If they fall out they take a while to regrow. Unlike shark teeth. The little baby hammerhead jaw my daughter’s friend brought from Mexico is a reminder that a shark can’t go long without its teeth, so it keeps an entire collection of them behind each pointy front tooth, just waiting to move up into place, when space is made. I’ve known some children who had what we called “shark teeth”—baby teeth that never fell out but just stayed there in front of their growing adult teeth. They feel to me a bit like backup-teeth. Not like the canines on that otter skull. They have no backups, waiting. I imagine if otters break a canine they’d suffer for a while. Maybe that’s why they’re so vicious. They can’t afford to lose a fight. The teeth of these skulls have such stories to tell, as much in the ways they’re similar to each other and to me, as in how different they are. Different lives; different needs; different priorities. But still with the same basic bodily needs.

You’d think there’d be few similarities between all these toothed animals and the bird skulls I have, or the barnacles and bivalves. But I see the similarities there, too. The beak of the eagle is in many ways a bit like its talons; you know how easily it would puncture and tear the body of that little flat-beaked songbird, holding one half under a talon and hooking the other half with its beak. The songbird’s skull is so light I can blow it off my hand by accident while trying to get the dust off. It’s made to fly. And that’s how it escapes the eagle.

The barnacle, of course, looks like a molar. Of course we know barnacles are filter-feeders, reaching out their elegant and feathery feeding legs to catch floating foods under the waves, but then why are they shaped like teeth? If you’ve ever stepped on one in bare feet you’ll know why. It’s protection. Same with a shark, or an otter. One of the ways human children defend themselves is by biting. That’s what teeth are for, too! And the bivalves. Nothing about them can be considered tooth-like, it seems, until you remember that there are razor clams. You don’t want to step on those, either! And sometimes, on shells, I find the little curved bits at the edge and remember that that’s where the clam’s mouth comes out to feed, or sometimes its foot. Because clams walk through sand. And fast, too, as you know if you’ve ever tried to dig for one.

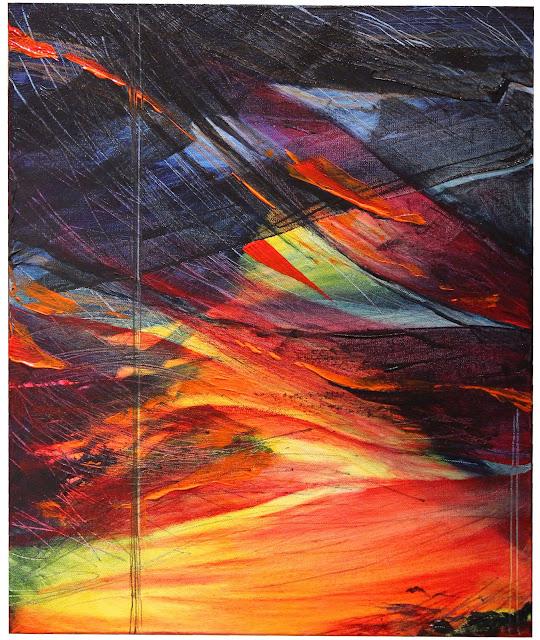

I look at all these bones and other body parts, and I feel connected to the world. I feel joyful that in our great diversity, we’re still all related; that our bodies have evolved to succeed in diversity and community. In this collection I also have lichens that remind me of our strength in living collectively with other species; I have conifer "berries" (not actually berries; I don't know what they are) that usually grow unnoticed in the tops of enormous trees, but which I collected off the ground. They remind me that there are beautiful processes we hardly notice for their being out of our usual sight, until a storm comes and knocks us all sideways, and we see things differently. I remember that all change is growth; even death. I remember that there is joy in just the smooth feeling of these bones; their lightness and their heaviness, the things I understand about them and the things that are mysterious to me. I remember the delight that I or others had in finding them, and I feel the sorrow that these lives ended, and the comfort of knowing our commonalities; the aliveness of just knowing we exist. I think of these things and I remember that everything is beautiful.