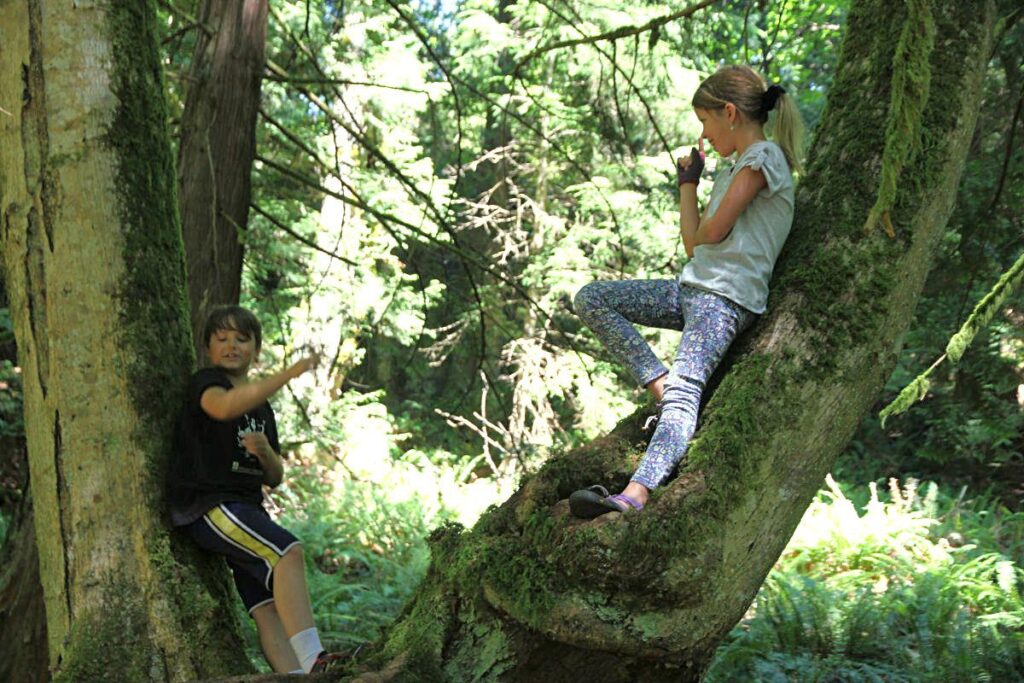

One of my favourite natural events is when the meadow floods. That's when the rain comes fast and the creek that normally flows through the alder forest comes out around the trees to run across the compact paths between long grasses, creating two- to thirty-centimetre-deep creeks that speed along, where in summer, bare-footed dogs and children run. In winter, I've run these temporary creeks in bare feet too. I know the feeling of the mud and wet grasses between my toes, and the fear of stepping in drowned dog poop. The joy of the immersion is too great to be daunted by the threat of poop. As I've grown older, though, I've come to appreciate the benefits of good rain gear and tall boots, which allow me to dive into my landscape without physical repercussions.

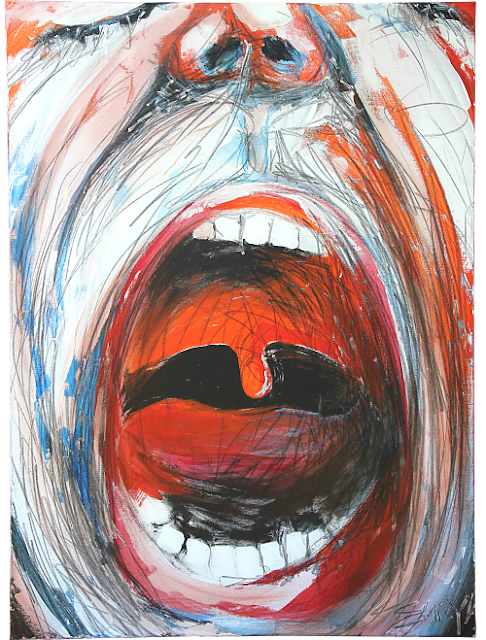

Diving into landscape is something I've been thinking about a lot, lately: How, through residencies and travel and schooling or working abroad, artists aim to really immerse ourselves in different landscapes, to come home refreshed and inspired; often longing to return again to the exotic and wonderfully wild places we visited. We make art during or after these travels that sometimes explores the longing, the wildness or the bodies-in-place-ness of where we were; sometimes the brokenness of our human emotional existence across a diversity of different locations.

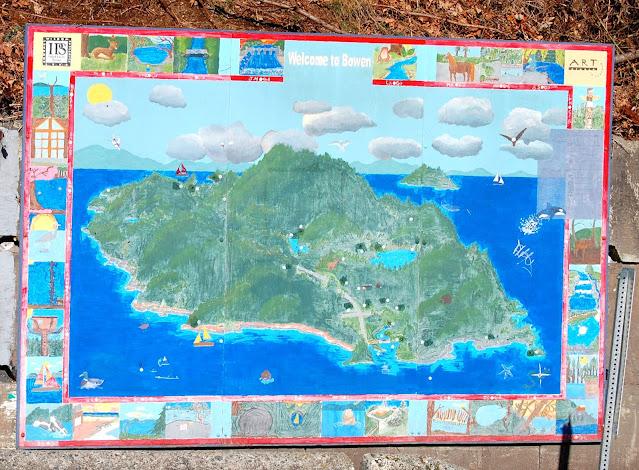

But pandemic and carbon-footprint considerations have led many of us to think deeply about the value and sacrifice of these muse-journeys. It's not only the air-travel that's a problem. There's also a problem with small villages taking a great percentage of their income from residence-tourism, or just tourism in general; when the actual residents of the community become dependent upon visits by people who will never actually become engaged in or contribute to the community as residents do, but only as grateful residence-artists. I live in a small community that gleans some of our income from tourism, and I know exactly how damaging a million tourist footprints are to the ecology of the place my own bare feet feel at home. I know how they take photos of this beautiful place, but never deeply understand the ecology; how they go home to write travel-blogs that extol the quaintness and quietness of my home but fail to capture the realness of our people; the political and social crises we feel, and even the imminent threat to the forests, fields, and beaches they're photographing. Once when I was small, my parents were out by the road cutting a tree into rounds for firewood–a gruelling job they did every year to keep our family warm–and some tourists drove up and stopped to watch them. They never got out of their car; just stopped to watch for a while and then drove away again.

I felt the other side of this problematic story keenly during my own residence in Amsterdam, a few years ago. I stayed and installed a project in the Goleb Project Space run by my friends Igor and Go-Eun. They welcomed and supported me graciously and while my experience was expansive, I noticed that the below-surface politics of the centre were very different than what I was experiencing as a visitor to the space. I wondered how my presence there had perhaps displaced others' work or intentions; how my ideas had changed the dialogue or intention of the group. Goleb is in one of the more mundane urban areas of Amsterdam, so I didn't think too much about my ecological impact, but one afternoon that changed. I was walking along the gracht (a small waterway for which we have no English word), getting closer and closer to an adorable family of coots, attempting to photograph them in what I thought was a remarkably interesting way, and a pair of men sitting on a bench nearby told me off for disturbing the wildlife. I reminded myself of the tourists I complain about, here in Canada. I had truly no idea of those coots' ecological value, nor who the guys on the bench were, or the stories they brought to that moment. It was all just an afternoon distraction from the project I was working on.

Then came the pandemic; the shutting down of most international travel. And the growing list of climate change disasters claiming our cultural, personal, and ecological heritage. Personally, I can't reconcile travel with artistic purpose anymore. I'm not even sure I can justify travelling overseas to visit family. So I'm thinking a lot about how we can be engaged and inspired by place without the inherent damage of travel.

What if travel isn't necessary to become immersed in landscape, or even to experience exotic places? We've already proven quite thoroughly that many of the business- and organizational-meetings we used to travel for can be done over the internet. I joined my brother's birthday dinner by video-chat, and have attended a couple of symposiums by Zoom. Artists have always found ingenious ways of making art in collaboration and across time and space through the mail, telephone, internet, and travelling exhibitions or projects. For me and many others, the creative solutions were often borne out of financial or temporal necessity, but now perhaps we can make these choices also out of concern for our future.

Plas Bodfa. Photo: Julie Upmeyer

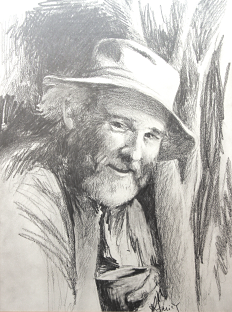

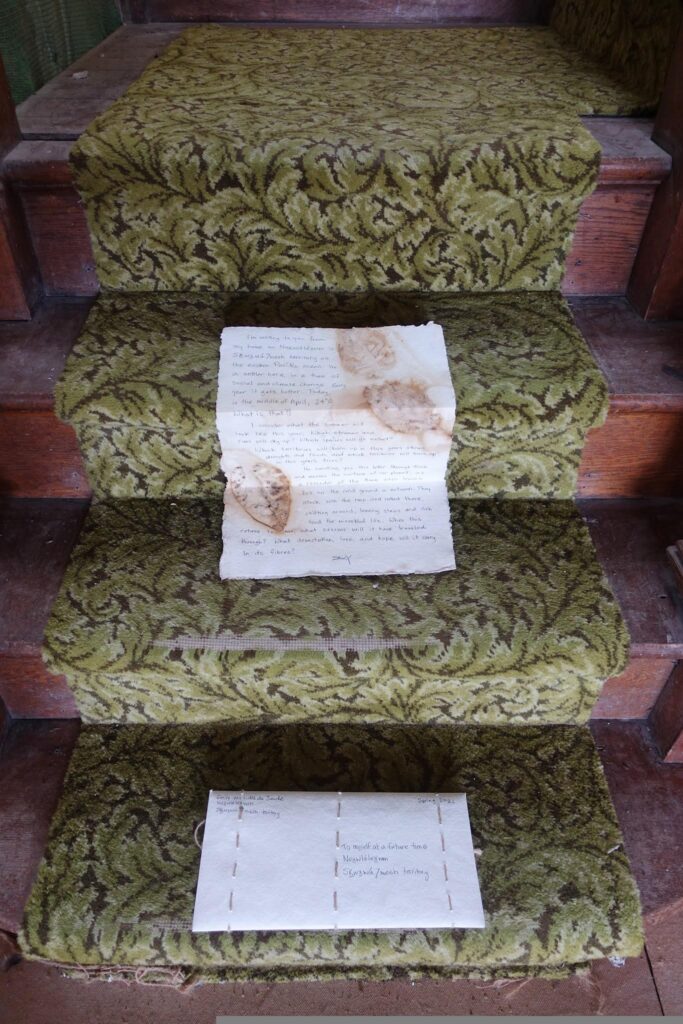

I'm including photos, here, of the Un-Boxing project I am honoured to be participating in, this year–a travelling box of works that examines ideas of place, travel, gifting, and time, as well as the delight of opening parcels. It seems a bit meta to me, and I can see how it might inspire a lot of searching and thoughtful dialogue. My entire experience of this show, so far, has been through others' lenses. For me personally it's reignited my passion for the hyper-local: If this is the view of my experience through others' lenses, what is the view of my experience, through mine? Or their experience of my contribution, re-experienced by me? I'm not a huge fan of navel-gazing, and now this sounds like meta-meta-meta, but maybe in trying to reevaluate our engagement with space and time and each other we can find new ways of experiencing.

In a symposium I attended virtually today about mobility, spatiality and virtuality in Iceland, artist Zuhaitz Aziku of Strondin Studio suggested that we need to "make people realize that they're buying experience. Because you cannot ever buy experience." The experience is what comes from what we put into anything. Whether Zuhaitz intended this or not, he made me realize that experience doesn't need to be far away to be exotic. I've been exploring the exotic of my own backyard for over forty years. How can there be anything exotic in my own backyard, when my body knows every inch of it so well? Because, as Zuhaitz helped me to realize, my experience of this place changes with every moment. My intention and what I take away depends on how I engage, and that, too, changes with every moment.

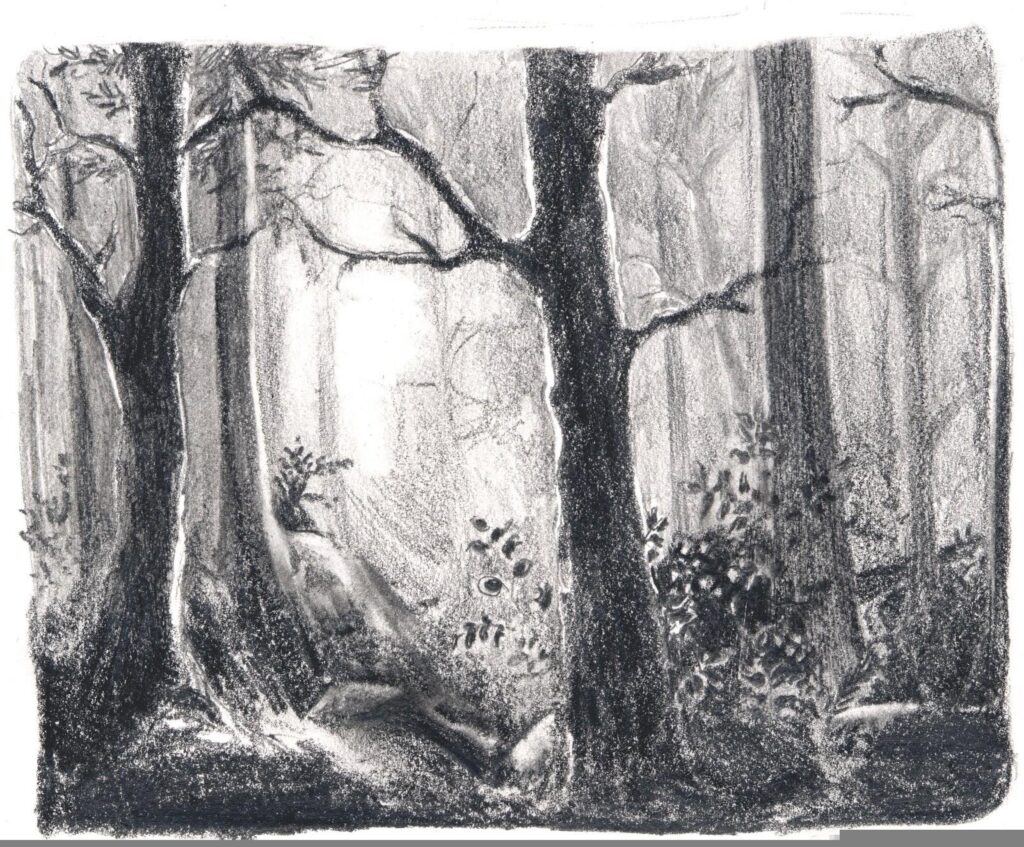

I think we travel in order to escape the routine of our lives; to break our minds from the same parade of sensual input we receive every day. It's easier to take a different view if we remove ourselves from our routines. But maybe that's just lazy. Maybe we can train ourselves to look differently every day; to pass the same places but never in the same ways. Maybe we can practice closing our eyes and listening to things we normally only see, or lying down in places we normally only stand. When I stop running through the meadow and crawl, instead, I discover that rodents have created pathways under the mat of grass. I find insects leaving trails of detritus inside these covered runways. It's like an entirely exotic world to the one I stood in just a moment before. When I run through that meadow in the flood, I feel a kind of sensory freedom that doesn't in any way compare to the way that grass feels in the summer. I wonder where the rodents go when the creek runs through their pathways. If I learn all of this, it won't be exotic anymore, but something new will happen tomorrow; there will be new questions and new experiences and new ways of engaging with this space. There will be new ways of experiencing and inspiring. I won't have to leave this place to find them.

Can I live in place in my own backyard and call it a residency? I sure as hell reside here, and the more I stay home, confined by pandemic and financial restrictions; my own ethical concerns around carbon footprint and supporting large corporate airlines, the more I see the value in this. Maybe we can adjust the expectation of worldliness in our artistic practices for the benefit of our common future. And far from becoming navel-gazing meta, our practices will expand into our spaces in a way that they never could when we were busy escaping for exotic experiences. We can use our art as a means for researching, understanding, and bettering ourselves and our own communities, in place.

Originally published in October, 2021.