The audio version of this story is available on my MakerTube.

Dear Little Emily,

You’re sitting on the floor of Mum and Pappa’s house, by the big brown bookshelf and the wide darker-brown row of Encyclopedia Britannicas. You have one open on your lap—number twenty-two—its huge brown covers rested against your bare knees, and you’re running your finger down the one of the many shiny, thin-paper pages of the PSYCHOLOGY section. Jeez there are a lot of things to say about psychology. But nowhere, not anywhere at all, do you see the word ‘psychosomatic’ popping up. Finally, after picking through hundreds of words you can’t bother to try out, you land upon this: PSYCHOPHYSICS, "a department of psychology which deals with the physiological aspects of mental phenomena." Mental. Grandma is a mental case, that’s for sure.

And amazingly, like the heavy book is calling her right out of crazy-land, the next listing in the book is PTARMIGAN. "A gallinaceous bird akin to the grouse." Whatever that means. It says it’s Gaelic, which is impossible, because you know ptarmigans are Canadian or Ukrainian. Grandpa is Irish and he never mentioned a ptarmigan. Grandma says ptarmigans live in Ukraine and in the Rockies, so. There they are.

But what the hell. Psychosomatic. It’s not even in the encyclopedia, right? Like even the definition of Grandma’s craziness is not in the book, that’s how imaginary it is. And the encyclopedia, now you’re nearly twelve, and it’s nineteen-eighty-seven, is the biggest, most trustworthy source of information in existence. As far as you know, little me, and you know more than some eleven-year-olds, but not nearly as much as you think you do.

You’re thinking about the last time you visited Grandma. Daddy dropped you off there for a sleepover, which seemed like a wonderful escape from the terrifying basement corner that you have to sleep in, at his house. But soon you realized there are other kinds of bad.

You sat in the wooden nook while Grandma smoothed her long, pearlescent nails. They’re three times as thick as your nails, because she’s old (though not as old as most Grandmothers, Mum says), and her nails are all covered with ridges, which she fills with layer upon layer of nail polish. You heard the plastic scrape of her nails; the rattle of her bracelets, and you shifted your gaze to the pink and turquoise squares of the kitchen floor. She was still talking, and you were getting tired. “The Devil lives in her,” she went on. “He lives in her mind and when she dies he’ll take her away to his lands.”

This wasn’t the first time Grandma professed to understand the Devil’s behaviour, and it usually somehow involved Mum. Mum says it doesn’t matter because we don’t believe in the Devil, so you sat quietly just waiting for Grandma to finish. “People who leave their husbands are evil,” she continued. “Your mother has the Devil in her heart, and you were born from that woman’s evilness. You have to pray to God to take it out of you.”

“I don’t believe in God,” you said, then, looking bravely up into Grandma’s wrinkly face; her nose kind of lumpy, in a way that made you think that must be the Ukrainian coming through. The angry concern in her sinister eyes leaked out the wrinkles of her face and into the perfect curls of her permanent-set hair. She looked like she might bite you, but you were too tired to care. It would be hours before Daddy would be there to pick you up, and by this point you thought you might fall asleep right there on the table, next to Grandma’s hands, her plastic bracelets rattling beside your head.

“Your mother taught you to say that. She put the Devil in you.”

“I’m so tired, Grandma,” you pleaded.

She looked up then, again, from her nails, and appeared surprised. “Oh, yes, dear. Would you like some Sprite?”

“Can I lie down on your bed for a minute?”

“Of course, doll-babe,” she replied. “I have to go call in the sun.”

You walked down the short hallway to Grandma’s bedroom as she slowly descended the brass-rattle staircase to the basement door, where the sun had begun to peek through, from the cedar trees, outside. “Come on, Sun!” She exclaimed. And, “oh hello, how’s your morning?” She asked of some random bird flying through her yard. And you lay there on her perfectly pink bed thinking about the mystery of fibromyalgia that caused Grandma to stand in the doorway and soak up the sun, every time it shone; that caused her, also, to keep her house a few degrees above normal, because supposedly it helped her pain. Grandma says she has fibromyalgia. Mum, Daddy, and everybody else say she has psychosomatic illness. It’s all in her head. And the Encyclopedia Britannica, for all its wisdom, has declined to comment.

You woke up with Daddy’s hand on your back. Somehow in your thoughts you’d slept two whole hours away, and it was time to go home.

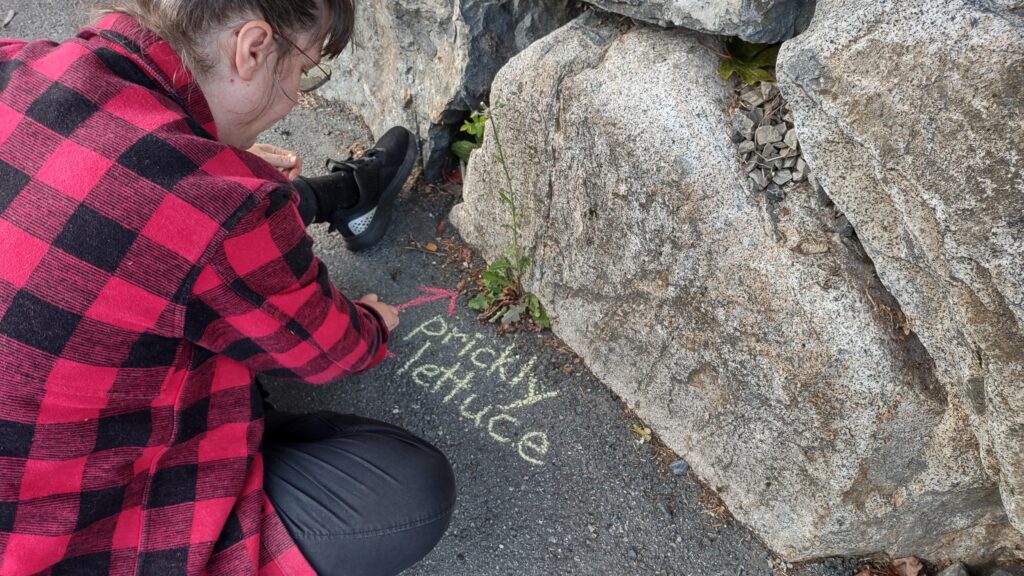

Home is a place of reason; a big tree-speckled yard full of food plants and flowering plants, some ponds, rabbits, chickens, a dog and a safe house to live in. No gods or devils, no ‘fairytales’, as Pappa calls them. You eat what you grow and you see how the actual world works. Everyone is upfront, or so they say. And illnesses are real—the kinds of things you can check with a thermometer and heal with cough syrup, chicken broth, and Earl Grey tea. Nobody has psychosomatic illness in this home. Nobody also calls in the sun, nor talks to birds.

Mum says it’s not really Grandma’s fault she’s crazy. She was born to parents who fled when Russia invaded, and that kind of family trauma can make people a little strange. Grandma says she remembers her own mother hiding up in the trees as her entire village was murdered. Grandma says this as if she herself was in those trees. Which is impossible, of course, since Grandma wasn’t born, yet. But she remembers. Daddy says Grandma is just wasting Grandpa’s money by keeping the house so warm. Pappa says it’s none of our business what she does with Grandpa’s money. You just wonder why Grandma doesn’t have her own money.

Times are going to change, little Emily. Here I am, writing you from twenty-twenty-five—a date you likely find it difficult to imagine. I found it difficult to imagine the year two-thousand only months before it arrived! But here we are. You’re grown. Me. We even had kids who’ve grown up, by now. Russia is beating the shit out of Ukraine, again, and Grandma didn’t die of war or fibromyalgia; she died of strokes, kind of, in the end. Mum died of a brain tumour, and so far as I can tell, the Devil didn’t take her, because I still hear her voice in my head, sometimes reassuring me, sometimes giving her opinions, and sometimes shrieking in alarm. Maybe it’s the Devil after all. Who knows. And I have fibromyalgia.

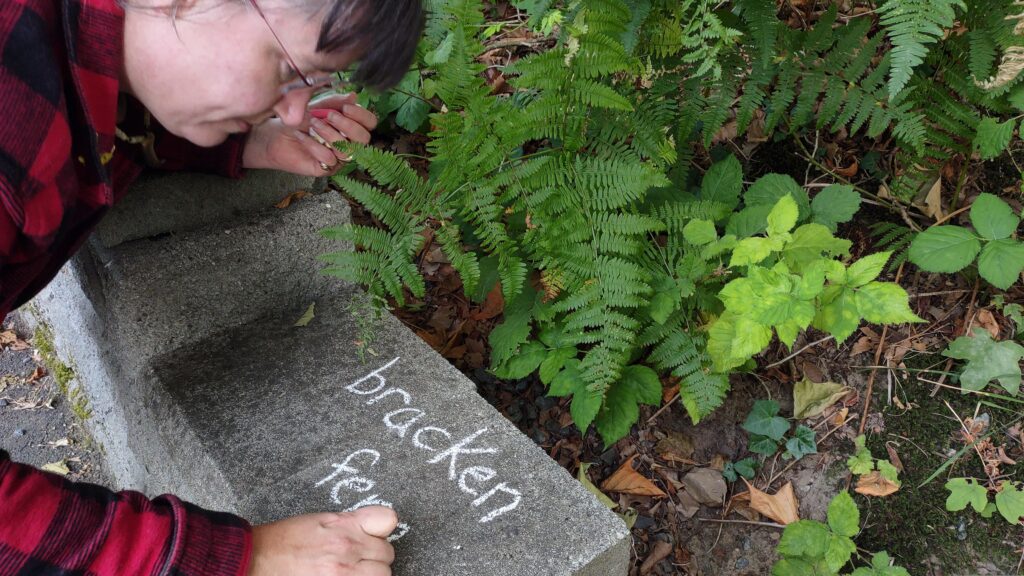

Yeah. You. You, when you’re grown up, little me, are going to have fibromyalgia, just like Grandma. And no family member is going to dare tell you it’s all in your head, because they’ll all watch you experience the pain and struggle that this stupid illness involves. In fact, one of the doctors who diagnoses you will mysteriously test a bunch of seemingly-random spots on your limbs for pain, and when they all hurt like bruises, she’ll explain that those pain spots are specific to fibromyalgia. She’ll then suggest self-treatment by using saunas, keeping your house warm, and perhaps also trying infrared therapy. Infrared light is contained in sunlight, little Em. The doctor will one day tell you to call in the sun. Well… metaphorically-speaking.

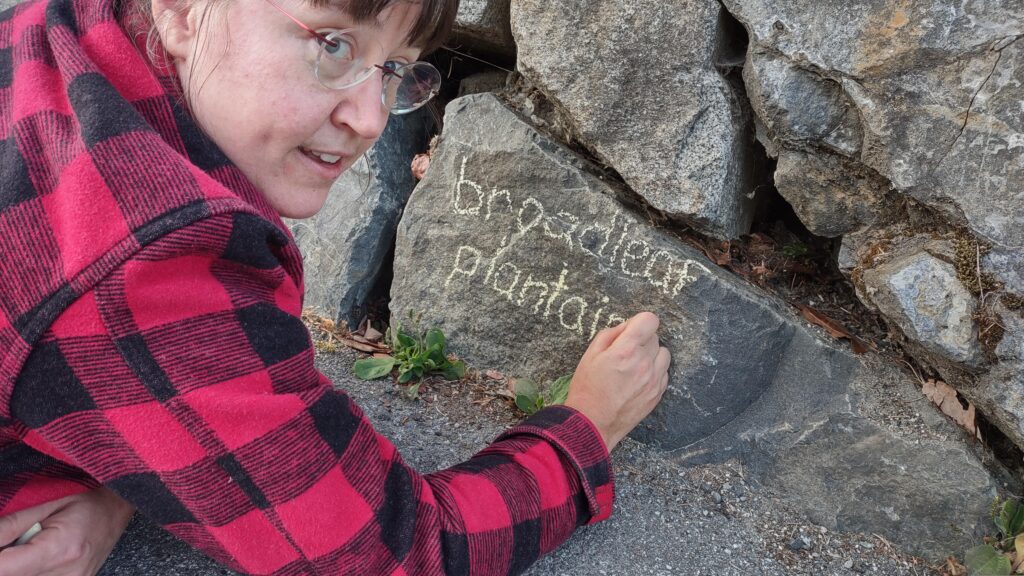

You’re not exactly going to start calling in the sun. But I do try to soak it in as much as my fair skin and hot flashes will allow. I sit out there on the porch, watching the yard of this place you grew up in and that I eventually raised our own children in. I see the garden where I still grow most of our food, and I watch Eamon, the raven who’s been living around here for a few years now, fly low over the sunflowers, and land under the walnut. “Good morning, Eamon!” I call. He doesn’t answer, but sometimes when I’m in the garden he calls, and I do answer. We play a game where I copy his calls, and he changes them. Or at least I think we play this game. Maybe it’s all in my head. Who cares.

Love, Emily